Strategic evidence-based diversity equality and inclusion solutions

Advice and guidance for difficult and sensitive topics

Contact us to explore how we can support you. |

Our Services

See below some examples of the services available.

Advice

Contextual advice on difficult and sensitive topics. Providing discrete guidance to manage reputational risk.

Audits, reviews and impact assessments

Root cause analysis of barriers to inclusion. Equality impact assessments for compliance with equality legislation.

Policy and guidance

Writing policies and guidance for employees and customers. B2B and B2C.

Employee engagement

Create diversity staff networks and analyse staff survey results.

Diversity data monitoring

Increase the percentage of diversity data you hold, compliant with GDPR.

❝ It is not our differences that divide us. It is our inability to recognize, accept, and celebrate those differences…

Audre Lourde

Our Blogs

Reparatory justice for people of Caribbean descent – a perspective from the diaspora

aishnine

Emancipation statue, Barbados When I was younger the thought of reparations and repatriation for the transatlantic slave trade seemed ridiculous....

Read More

Trans Day of Visibility (TDOV) and healthcare – not a debate

Aishnine Benjamin

Today, 31 March is International Trans Day of Visibility (TDOV). The topic of trans, transgender and non-binary equality is sensitive...

Read More

Setting the foundations for tackling race inequality in the workplace

Aishnine Benjamin

Organisations often know they have a problem with race equality. Their employee data, seeing that people from different racial groups...

Read More

Get In Touch

About

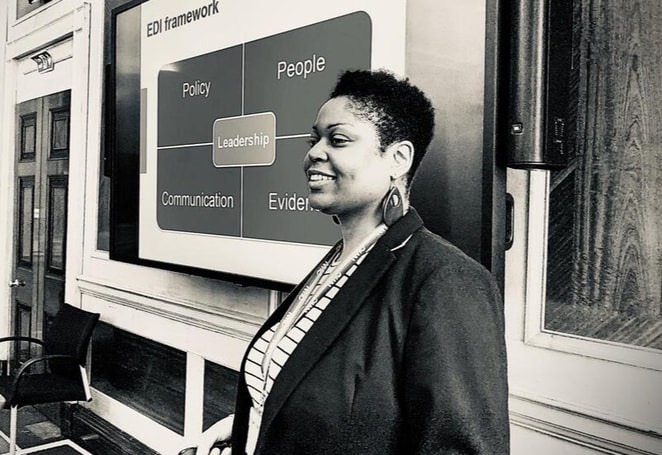

Pieris Paths

Led by Aishnine Benjamin, equality, diversity and inclusion professional in healthcare. Extensive equalities-related work experience, voluntary work advocating for social justice and academic background in racial equality and human rights